Inspecting the Olympic

This week, OTM visited the Olympic, a 200-foot decommissioned Washington State Ferry with an eight-cylinder Fairbanks-Morse diesel engine. It’s currently tied up at the ferry graveyard in Eagle Harbor on Bainbridge Island, as it has been since the mid-1990s. It’s starting to show:

We were asked to inspect the engine room systems to evaluate whether the engines were still operational. Apparently, the boat is currently owned by a non-profit foundation that sells boats at a profit to fund scholarships and other worthy causes, and they have a buyer lined up on the condition that the engine works and she can be re-commissioned. We started the process with some background research. As usual, the Evergreen Fleet proved invaluable, as did the venerable Ferryboat Book.

The MV Olympic was built in Baltimore in 1938 as the Gov. Harry W. Nice, with a riveted steel hull and a direct-reversing Fairbanks-Morse engine rated for 1,400 horsepower at 300 RPM. She and sister ship Gov. Herbert R. O’Conor worked the Kent Island-Sandy Point Bay route across the Chesapeake Bay. In 1952, the route was replaced by the Bay Bridge and the two ferries were sold to the Washington State Ferry system. Renamed Olympic and Rhododendron, the ferries went into service in 1954 to work the Clinton route. In 1969, the Kulshan started on the Clinton route, and the Olympic became the overflow boat. In 1974, she was moved to the Port Townsend-Keystone route, but when the new Issaquah-class ferries took over the route in 1979, the Olympic was scheduled for retirement.

In 1983, the Rhododendron was mothballed, but the Olympic kept running despite Coast Guard concerns over operating a single-engine ferry (following an engine shut-down that left her drifting in the Sound for three hours before engineers brought it back online). She was moved to lower-traffic routes (mainly the Point Defiance run) and scheduled for refurbishment with the Rhododendron, but cost over-runs on her sister ship meant that the Olympic was mothballed in 1993. She was surplused and auctioned off in 1997, and has been in Eagle Harbor since.

I don’t think that the boat’s been touched since she was mothballed the second time – she even has newspapers from her last cruise laying in the lounge:

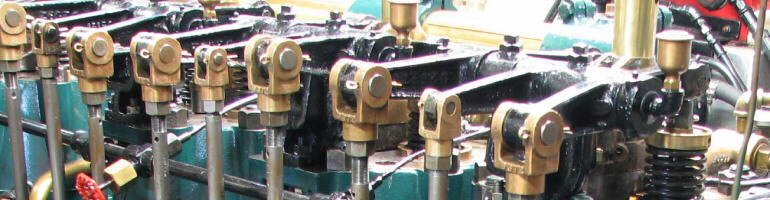

More importantly, she still has the original Fairbanks-Morse diesel, an eight-cylinder with a 16″ bore and 20″ stroke:

The only major problem that I found is that the main diesel-powered air-compressor is missing. This is really the key to the boat, as, like almost any boat powered by a heavy-duty diesel, the Olympic needs compressed air to power nearly all of its major systems, including the generators and main engine. It still has two electric air-compressors, but they require 120 volts DC electricity to run, which in turn can be supplied by one or both diesel generators, but these each need compressed air to start. Oi.

As far as I can tell, everything else is in decent condition and looked like it had been well-maintained during its working career, but without that main air compressor we couldn’t turn it on and tell for sure. Anyone getting the boat back to operational condition will be fighting corrosion every step of the way, and that every valve will need to be exercised and every pump will need to be freed up before putting the systems back online. It also means the new crew will need to do a lot of cleaning to make it possible to work in the spaces:

After the trip, I put together a list of recommendations for the organization and any potential buyers. Most importantly, I told them to change one of the small air compressor motors to AC power and a voltage that can be provided at the dock, in order to let them exercise the machinery and demonstrate that the main engine runs (or doesn’t run, whichever the case may be). Both DC air compressors look like they’re fine, so just switching out the motor should be pretty easy:

Here’s the total process that I recommended:

- clean the vessel, giving it at least a once-over

- change the air compressor motor

- start the auxiliary generators

- put systems on line and test

- install switches for steering and jury rig manual wheel; test steering

- blow down main engine; bleed fuel lines; repair oil filter

- tow the vessel out and test-run the main engine

- re-assess the condition and determine the next steps

This would be a great project, since the Olympic is a great boat in very good condition, considering that it’s been basically untouched at the dock for over ten years. It’s also pretty historically significant as an example of state-run ferries from the 1930s to 1970s, since most of the other ferries of this era have been re-powered, scrapped, or otherwise lost. I hope that the potential new owners get as excited about the project as I am, and that they call me in as a specialist to help re-commission the boat. Stay tuned (I hope)…

Work continues on the Catalyst

I spent the rest of the week on Catalyst, continuing to file and sand the oil hole ridges off the crankshaft. I feel like I’ve been sanding forever, and I’ve still got some left.

The rod bearings also came back from Everett Engineering, freshly babbitted and looking good. I inspected them again and found two things. First, one of the check valve balls was rusty and sort of pitted. These check valves are in the top half of each rod bearing, right against a hollow tube that runs up through the rod itself to the wrist pin. This keeps the rod full of oil after shut-down, so that oil gets up to the wrist pin as soon as pressure comes up. Since balls for the check valves are cheap, I bought new ones for all six bearings and put them in.

Second, some of the peel packs, which are a set of shims stuck together with solder that fit between each half of each bearing set, were replaced with plain shims. This isn’t really a big deal, except that I like peel packs better. I might get new ones, but I haven’t had the time to look into yet.

We also decided to send some of the cam followers and wrist pins to be flame-sprayed. In preparation, I stripped the followers and sent the wrist pin bushings to Asco to be honed down. The bushings (which are made of brass) wear down unevenly during normal operation, so it’s important to get them straight and round before the wrist pins are fit in. Honing is done with a specialized tool made up of three or four stones (they’re sort of leg-shaped) that push against the outside of the bushing and grind a small amount of material off while they turn.

I sent the wrist pin bushings off while they were still in the rods:

OTM’s tips for getting your heavy-duty through the economic crisis

All owners of heavy-duty engines are going to feel some pain from the current tough economic times, but OTM has some easy tips to help your engine (and your boat) survive the recession.

Get to know your boat, and want to get to know your boat. This will not only save money, it will make cruising safer and more pleasant. Get a flash light and get under the deck plates.

Clean the whole boat – especially the engine. I cannot overemphasize the importance of cleaning. This simple task addresses nearly all problems with the engine or other systems. If cleaning doesn’t actually solve the problem, it at least will keep the problem from getting worse – plus it makes it much easier to find and note problems so they can be addressed before they get worse. I have heard customers say “I haven’t wiped down the engine for a while so you [the mechanic] can find the leaks easier,” but I then have to spend the whole day cleaning the engine in order to find the leaks. This adds to the bill. It’s also just easier to work in a clean engine room, so the mechanic will be more efficient and productive than in a dirty engine room.

Simplify. In all situations, it’s important to just keep it simple. Good examples include:

- selling the crane and using davits and block and tackle instead. It looks more elegant and is not much more work (and you hardly ever lower the boats, anyway)

- removing the hydraulics in a small boat, because you don’t need them. Hydraulic systems are very powerful and few small boats need that kind of extreme power

- forget about the second radar unit, and clean the windows in the wheel house instead

- insist on smaller systems. Try to install “normal” systems: no one thinks a whiz-bang radar-guided autopilot is impressive unless the rest of the boat operates flawlessly, is used often, and has demonstrated a need for the device

Focus on need. Often the neatest-looking boats are that way because of how the owners meet their needs simply. I mention often how I like the “lived in” feeling of any structure that is well worn in. Another example is a small line attached to a door and frame to keep it from opening too far and slamming, which is a simple and elegant solution. A megayacht outfitter will try to get you to spend $2,500 on a mechanism to accomplish the same task, which needs to be greased monthly and rattles at full speed.

Break down jobs. See the trees in the forest and make a list with four-hour tasks. Don’t put things on the list like “rebuild engine”. It’s okay to cruise with broken parts as long as you know your limitations. Break the jobs into manageable pieces, and do some now and others next year.

Stay busy. If laziness sets in, the complacent attitude will sink the boat. Stay on task, look at the list, and keep making forward progress – even if it’s slow.

If you follow these tips, you’ll both keep your engine in good shape without spending too much money, and get greater satisfaction out of being proud of the work put into your boat.